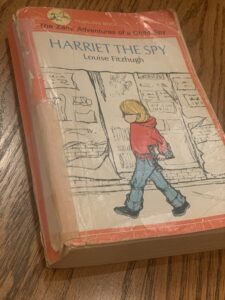

When I was growing up, Harriet the Spy was one of my all-time favorite books. I read it so many times that the spine cracked. (I actually still have my copy of the book – scroll down for a picture of it.) It’s the story of Harriet, an irreverent, nonconformist eleven year-old girl who keeps notebooks detailing the goings-on of her Yorkville neighbors and containing unflattering comments about her classmates. One day, her notebook is confiscated and read, and Harriet must suffer the fallout from this unfortunate discovery. In the end, she learns the value of tact, compromise and the well-placed apology, as she tries to get back into her friends’ good graces. But who was the creative genius behind Harriet The Spy and its classic illustrations? She was Louise Fitzhugh, the subject of Leslie Brody’s biography, Sometimes You Have To Lie.

Why I picked it up: When I was offered the chance to be part of the blog tour for Sometimes You Have To Lie, I eagerly accepted the invitation, as I wanted to learn more about the author whose book I had long loved.

Louise Fitzhugh was a complicated woman. Born in Tennessee in 1920s to a mismatched couple who divorced soon after, she was raised by her father’s wealthy family and kept from seeing her mother until she was basically an adult. She never felt comfortable in segregated Memphis and moved during college to New York, where she eventually settled in Greenwich Village. Fitzhugh was an artist, dabbling in everything from painting to murals to book illustrations and, eventually, fiction. Harriet The Spy came out in the mid-60s and reflected Fitzhugh’s generally iconoclastic view of the world. She disliked artifice, convention and predictability. She never hid her lesbianism and had several long, committed relationships with women. She dazzled and entertained her friends with her passion, humor and talent, but she could also be impetuous and flighty.

Brody’s memoir, compiled from a wide range of interviews with Fitzhugh’s family and contemporaries, explains how Fitzhugh’s roots turned her into the person she became. Her father, in particular, was a smart but insecure man whose insistence on control and propriety was soundly rejected by his daughter (and would have been by Harriet, too). His mother, Fitzhugh’s grandmother, was kind but eccentric, and she too found a place in Fitzhugh’s writing over the years. Harriet’s beloved nanny, Ole Golly, was an amalgamation of caregivers who had shown Fitzhugh kindness and affection in her childhood – something she had lacked from her own parents.

Brody was clearly taken with her subject, and her writing is lively and detailed – sometimes overly so, as there is a fair amount of information in Sometimes You Have To Lie that could have been pared back or eliminated. And because Fitzhugh was reclusive and rarely gave interviews, Brody was often left to guess about Fitzhugh’s innermost thoughts. But for diehard Harriet fans – of which there are surely millions – Sometimes You Have To Lie is a rewarding look at the woman who conjured up such a compelling heroine.

Sometimes I Have To Lie was book #2 of 2021.

About Me

I have been blogging about books here at Everyday I Write the Book since 2006. I love to read, and I love to talk about books and what other people are reading.