Hausfrau is the story of Anna, an American expat married to a Swiss banker living outside of Zurich. She stays at home with her three children, living the bored, lonely life of a suburban housewife who – even worse – can’t speak the language of the country she’s living in. Anna is depressed, antisocial, and self-absorbed. Her husband, Bruno, is brusque and unemotional, and while they occasionally connect sexually, there is little emotional intimacy between them. Anna embarks on a series of reckless affairs, most of which don’t bring her any satisfaction or fulfillment beyond the fleeting and physical. Hausfrau follows Anna for six months or so as she spirals downward, increasingly less able to control her impulses and further removed from her responsibilities to her family. Even after she resolves to recommit to her husband, she doesn’t untangle herself completely from her affairs and makes poor decisions with serious ramifications.

Anna is relentlessly passive, letting things happen to her and exerting almost no control over her reactions and participation. She enters into a friendship with a woman from her German class almost entirely unwillingly, letting herself be sucked in to the relationship with no enthusiasm. She knows that her mother-in-law, who takes care of her young daughter on her many afternoons away from home, is disapproving and resentful, but she never confronts her or apologizes. And she endures her husband’s bad moods and benign neglect without complaint or confrontation. She participates in most of her life with the barest of energy, with the exception of her affairs, which at least merit her physical presence.

Interspersed with Anna’s story are excerpts from her sessions with a psychoanalyst, who tries to help Anna understand herself better by questioning her motivations and frustrations (and basically answering all of Anna’s questions with her own).

People seem to have strong reactions one way or the other to Hausfrau. Either they love Essbaum’s poetic writing and exploration of morality, or they hate Anna and find the book too dark and sexually graphic. I fell mostly into the first camp. I liked the writing a lot, found the setting remote and interesting, and thought that Anna was interesting in a “I can’t look away” kind of way. She is maddening and not very likeable, to be sure, but there were some universal themes in the book that I enjoyed exploring. I did not like the psychoanalysis sections. I didn’t understand a lot of them, or found them boring, or both. But they do help to paint the picture of Anna’s despair and desire to get at the heart of something, even if she doesn’t know what it is. She also wasn’t totally honest with the therapist, so the utility of the sessions was necessarily limited.

I listened to Hausfrau mostly on audio. The narration by Mozhan Marno was excellent. She mastered many accents, especially Bruno’s and the therapist’s, and they all seemed totally authentic. I loved her Bruno – she just captured him perfectly. One challenge to the audio – the book jumps around a lot, both in time and in plot thread, so there’s a risk that the audio version would be challenging to a listener without paragraph cues. But I found it really easy to follow. This is a bleak book, but the narration gave it life and empathy.

MILD SPOILER AHEAD

I’ve waited a week since finishing Hausfrau to write this post, trying to see how it would sit with me after some time off. I think I liked it more in the beginning than in the end. Ultimately, Anna’s situation was just too hopeless. I wanted some redemption, some change to make her life more bearable, but it never came. In fact, it just got worse. Essbaum’s writing is amazing, and there is a lot of compelling stuff in here, but it was too bleak even for me. (And that says a lot.)

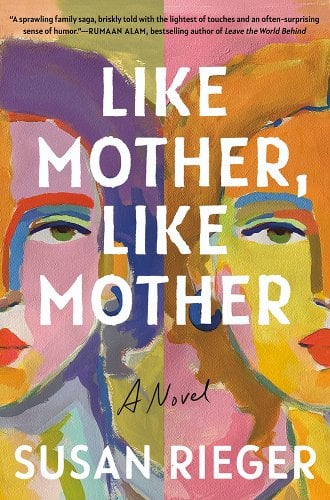

(How gorgeous is that cover, though?)

About Me

I have been blogging about books here at Everyday I Write the Book since 2006. I love to read, and I love to talk about books and what other people are reading.